|

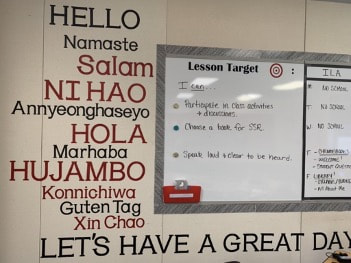

I'd like to highlight two teachers who used their walls very effectively to welcome new students who were from different cultures than them. One ILA teacher at Fowler Middle School put the phonetic spelling for "welcome" in the languages of her new students on her wall. This allowed students who did not speak those languages to greet the newcomers in their home language. Often, teachers will ask me: What can I do to help newcomers feel safe enough to speak out in class? Sometimes I tell them: that it's not about what you train the new students to do, it's about what you train the "old" students to do: teach them how to welcome others from another culture. We, teachers, love to put our time, effort, energy, and money into creating a welcoming environment for our students on the first day of school. Nevertheless, no matter how “cute” and creative the decoration becomes, the physical design of our classrooms often unwittingly becomes an extension of our worldview and dominant culture (Hammond: 2015:19). Well-meaning teachers look for ways to decorate their rooms in ways that connect with and represent the diverse cultures of their students. This is becoming easier and easier to achieve with the wealth of culturally diverse resources in education. Yet, a cultural disconnect may still remain.

One teacher commented to me: “I am really trying hard to connect with the culture of my students. I even put up LatinX heroes for them in the classroom, like Frida Kahlo! But guess what - they didn’t even know who Frida Kahlo was!” This example illustrates the importance of discovering the students’ stories and the assets of their particular aesthetic or culture. Perhaps the artists that they admire are more in line with “Bad Bunny” and “Becky G,” and the only to find this out is through the practice of “noticing” (which we will discuss in more depth in chapter five (“Show the Student She is Seen”). In the meantime, this problem is mediated by the teacher taking a personal interest in the artists and figures from the cultures of her students. Instead of guessing who the students will like, the teacher highlights the artistry of someone she herself appreciates. This is so much more authentic (and children can sniff out inauthenticity better than anyone). I have seen a first-year teacher do this very effectively with his “hero wall.” When a student points to Kendrick Lamar, and says: “Who is that?” The teacher responds with: “Oh, he’s a master storyteller with a prophetic voice for our generation,” rather than: “he’s a black rapper from Compton, I put him up because I thought you might like him.” When students realize that the representation is personal to the teacher, this not only creates a connection with the teacher: “He is like me,” but it affirms the assets and innate beauty in the student’s own culture. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorElise White Diaz is an Educational Consultant with Seidlitz Education, specializing in trauma-informed multilingual education. CategoriesArchives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed