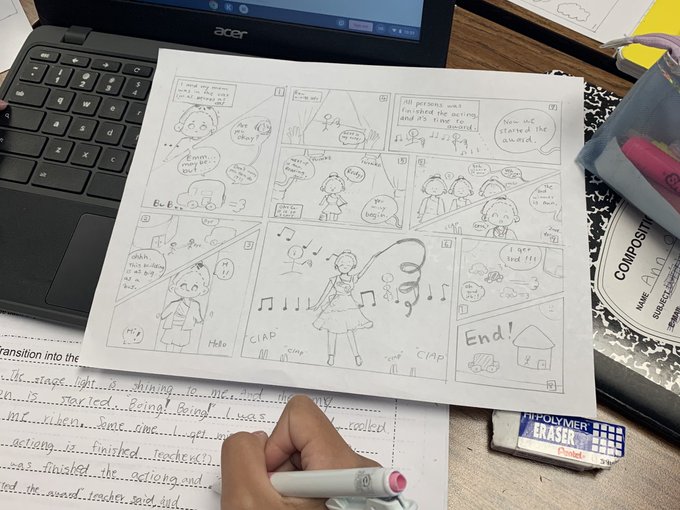

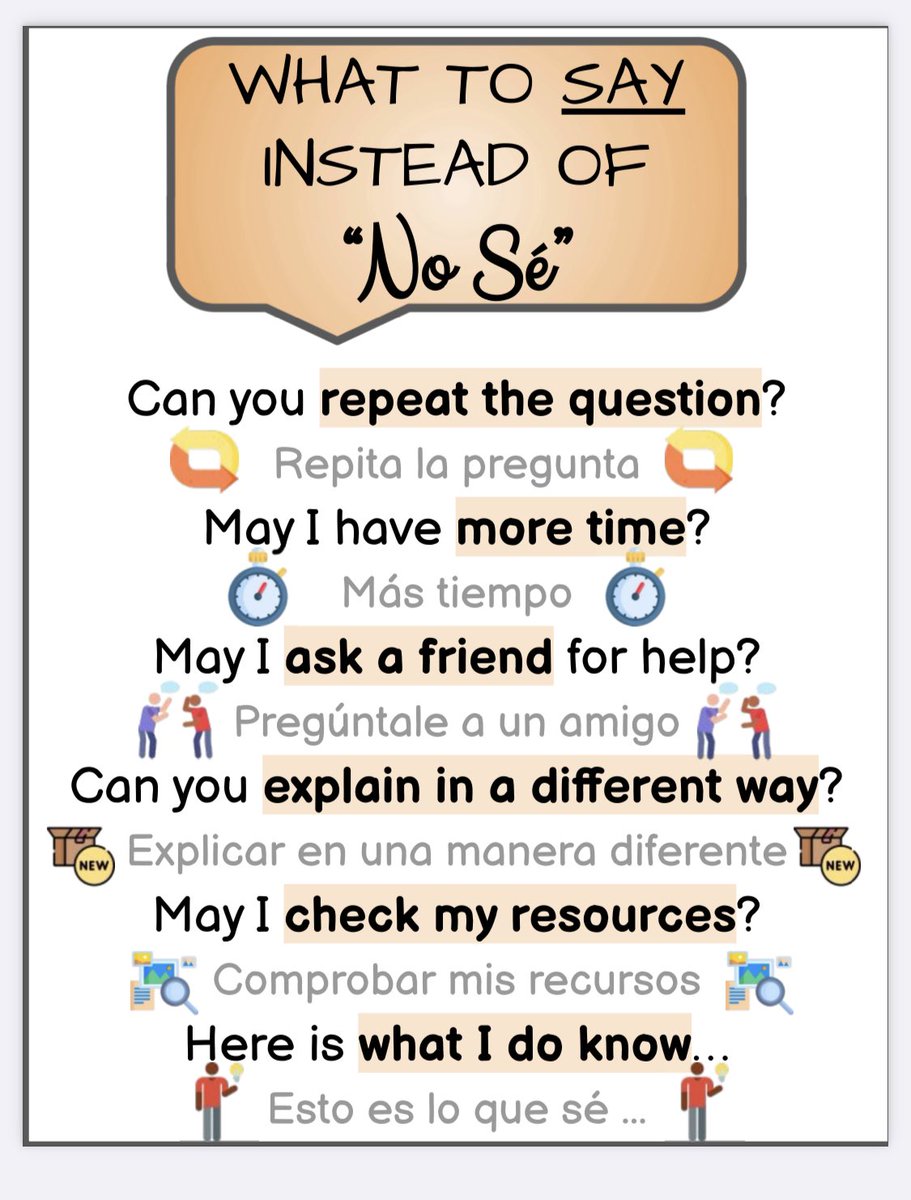

Beginners tell their stories by illustrating a graphic novel. Each panel corresponds to a different element of plot (which they learned about read graphic novels and watching Pixar shorts). As they illustrate their stories, students point at their pictures and attempt circumlocution (a roundabout way of speaking if they don't have the vocabulary needed) to explain what is happening in the picture. The teacher helps them find the words: "Do you mean "ribbon dancing?" "Yes? This is how you write it." Then the student copies down the text she co-created with the teacher and practices reading it for fluency. This activity is wonderful for students learning the English language because it allows them to practice in each language domain (speaking, listening, writing, and reading), and also provides context to give meaning to the words they are discovering. This activity is effective for third grade through high school. Many panel options be found simply by googling: "graphic novel template." How would you incorporate an activity like this into your lesson planning? I talk to my own kids about what I'm doing in the classroom, probably too much. I do get a lot of good ideas from them. One time I was talking to my son and explaining the theory behind the "What to say instead of "I don't know," poster, which I encourage teachers to have in their classrooms. He remarked: "Mom, are you really training kids to say: "May I please have some more information?" (This was said sarcastically). "What, are they talking to the Queen of England? Is this a Charles Dickens novel?" (I wish!) He went on:

"I hate it when teachers correct me when I'm asking to go to the bathroom ("May I..") He's actually not wrong in this criticism. Linguist Stephen Krashen describes how ineffective it actually is when we teachers correct students' grammar in the classroom in this way, but I'm getting off-topic. My son's point is that he wanted to give students the meta-cognitive tools to think about why they don't know the answer, or what they need to find the answer, but spoken in their own way. Since that fateful conversation, I have been encouraging teachers to NOT put up the standard "Instead of "I don't know poster." Instead, to make the poster along with their students. One teacher I worked with in Texas (Dominque Phifer), created this beautiful poster (above) for her newcomer, predominantly Spanish-speaking classes. When teachers make their own posters with and for their students, the responses vary. Sometimes the poster might say something as simple as "Help, please" (if you have a newcomer just at the starting line of language learning, with a very high affective filter). Or perhaps the poster says: "Point to what you need." The point of these posters is to teach students a metacognitive skill and to remind teachers every student has the capacity to find the answer, with support. My son was right (although I would enjoy everyone around me speaking as if it was 18th-century England). Sometimes we get lost in the product and forget about the process. SWAP Out the "American" Names for Common Names in Your Students' Cultures

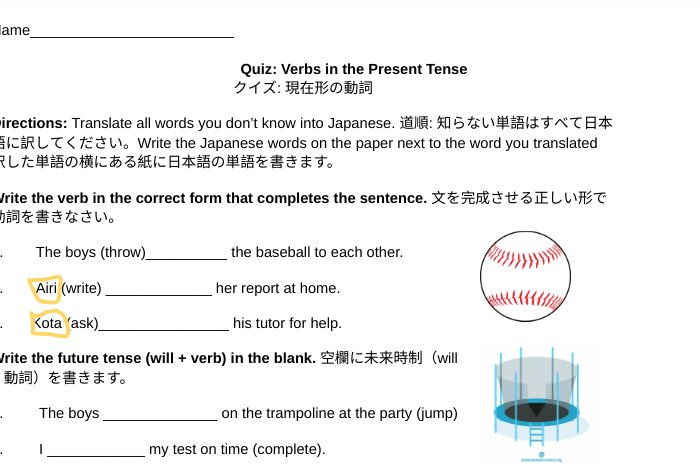

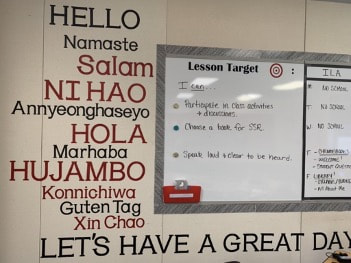

When accommodating a quiz for newcomers, swap out the "Heather's" and "Brian's" in your examples for common names in their culture. One less word to translate, and helps them feel a greater sense of belonging. There are so many times I have been helping a newcomer read a grade-level text in their core classes, and they ask me: "What is a 'Stacy'?" This is a very easy thing for teachers to do, and that has a great impact! I'd like to highlight two teachers who used their walls very effectively to welcome new students who were from different cultures than them. One ILA teacher at Fowler Middle School put the phonetic spelling for "welcome" in the languages of her new students on her wall. This allowed students who did not speak those languages to greet the newcomers in their home language. Often, teachers will ask me: What can I do to help newcomers feel safe enough to speak out in class? Sometimes I tell them: that it's not about what you train the new students to do, it's about what you train the "old" students to do: teach them how to welcome others from another culture. We, teachers, love to put our time, effort, energy, and money into creating a welcoming environment for our students on the first day of school. Nevertheless, no matter how “cute” and creative the decoration becomes, the physical design of our classrooms often unwittingly becomes an extension of our worldview and dominant culture (Hammond: 2015:19). Well-meaning teachers look for ways to decorate their rooms in ways that connect with and represent the diverse cultures of their students. This is becoming easier and easier to achieve with the wealth of culturally diverse resources in education. Yet, a cultural disconnect may still remain.

One teacher commented to me: “I am really trying hard to connect with the culture of my students. I even put up LatinX heroes for them in the classroom, like Frida Kahlo! But guess what - they didn’t even know who Frida Kahlo was!” This example illustrates the importance of discovering the students’ stories and the assets of their particular aesthetic or culture. Perhaps the artists that they admire are more in line with “Bad Bunny” and “Becky G,” and the only to find this out is through the practice of “noticing” (which we will discuss in more depth in chapter five (“Show the Student She is Seen”). In the meantime, this problem is mediated by the teacher taking a personal interest in the artists and figures from the cultures of her students. Instead of guessing who the students will like, the teacher highlights the artistry of someone she herself appreciates. This is so much more authentic (and children can sniff out inauthenticity better than anyone). I have seen a first-year teacher do this very effectively with his “hero wall.” When a student points to Kendrick Lamar, and says: “Who is that?” The teacher responds with: “Oh, he’s a master storyteller with a prophetic voice for our generation,” rather than: “he’s a black rapper from Compton, I put him up because I thought you might like him.” When students realize that the representation is personal to the teacher, this not only creates a connection with the teacher: “He is like me,” but it affirms the assets and innate beauty in the student’s own culture. World Cup fervor came on strong last spring. In my own house, there were lots of hoots and hollers and teenage boys with their t-shirts over their heads flying around the living room (I'll never understand this fútbol tradition. My cousin from Panama who plays soccer for a US university tried to explain it to me. "That's just what you do," he said. Anyway, I knew I had to leverage this excitement in my own ESL classroom, where "football" meant something very different from the way most understood "football" in Texas. Here's what we did: 1. Pick an engaging photo (from Google Images, ahead of time). It had to have Messi or Ronaldo in it (of course). 2. As a class, I asked students to list the nouns (or things) they saw in the photo. Some of these words they knew: "leg." Some of the words they didn't know: "That thing he wears here (points to leg), up high to protect" Me: "Sock?" Student: "No, not exactly..." Me: "Shin guard?" Student: "Yes! That's it." Students provided the words (with help, sometimes). I wrote them on the board because this group of newcomers did not know how to spell the majority of the words. 3. Then we did the same thing with verbs and adjectives. This is called the "Picture Word Inductive" Model, and Valentina Gonzalez gives a beautiful description of it here. Here's what came out of it:There are two main objectives in this writing prompt: (1) how to convert dialogue bubbles to properly punctuated dialogue on the page. (2) How to make inferences about characters' feelings.

This page comes from the popular graphic novel, "New Kid." |

AuthorElise White Diaz is an Educational Consultant with Seidlitz Education, specializing in trauma-informed multilingual education. CategoriesArchives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed