I love a good 3-in-1. A hydrating lip shine that also delivers color and can be used as a cream blush? Yes, please. How about a sunscreen that soothes my rosacea, and includes a bit of tinted coverage? Most definitely. My husband likes to take the 3-in-1 too far. He showed me this 13-in-1 product on Reddit he was considering purchasing. I’m glad it doesn’t exist! What if we could do this same thing in the classroom? Deliver lessons that align with our content standards, support language development, and coach students in emotional literacy? I’m all in! The key to wrapping these three power objectives together is to begin by choosing a content standard that pairs well with emotional literacy. Here is an example from a seventh-grade science class in their unit on body systems. In terms of which emotional literacy targets to teach, CASEL, a nonprofit organization working to advance the science and evidence-based practice of social and emotional learning, has identified a framework that is widely used to develop emotional literacy standards. Read more here: https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/what-is-the-casel-framework/

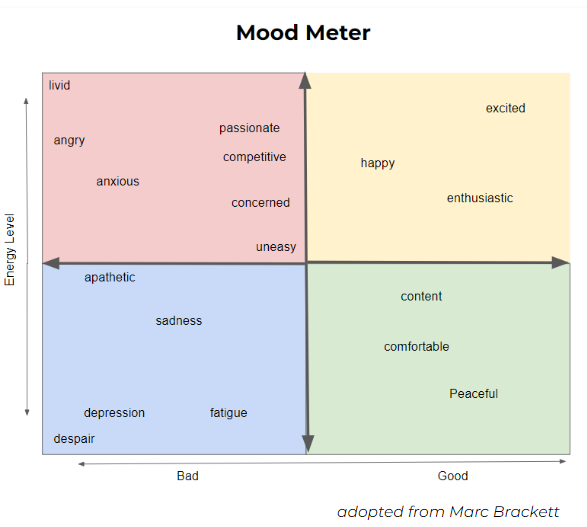

After the content and emotional literacy target have been identified, develop a language target, identifying which language domains you would like students to use to show that they have met the content objective (listening, speaking, reading, or writing). If it is an expressive language target (speaking or writing), include which words you would like students to use. See the full lesson plan here: https://padlet.com/elise266/discover-connect-respond-hh7rquei3uiua4fj And keep checking back for additional lesson ideas in other content areas. I looked at the wall clock and the precious 35 minutes I had left of my conference period and waited for the teenage girl to get to work. Thuy made no movement or indication that she was going to do so, not even picking up her pencil. Instead, she just stared straight ahead, eyebrows raised in defiance. “Thuy, do you know how to do this first one?” I pointed to the first math problem, and she visibly scooted a little further away, turning away. I took a deep breath. I would not be deterred. I picked up her pencil and pointed to the first problem. “MMNHH!!!” Thuy growled at me, snatched her pencil out of my hand, and folded her arms across her chest, ensuring that I would not get that pencil. I felt irritation rising in my belly like bile and closed my eyes for a moment. Whenever we serve children from hard places, we need to tune into ourselves and notice what the children’s response elicits in us. Here is a strategy to do so, one that I have often used at the beginning of a busy school day during the flag salute and the following “moment of silence.”

Once I cooled down, I looked at that red sticky note with curiosity. Why did a thirteen-year-old girl struggling in a new culture trigger me so much? My reaction felt exaggerated. What was it about that interaction that made me so angry? Identifying the emotion within us is the first step. Stay tuned for what to do next. You have been working so hard this year: loving on kids who might not get that attention and high expectations from anyone else.

I know that you feel discouraged, and like you are not making a difference. I know that you have just received a disappointing appraisal. And your appraiser’s comments go against everything that you have learned about teaching multilingual students. Your appraiser told you: less small group conversation, instead instruct the whole group and lead from the front. I wanted to remind you that appraisers are themselves human, and sometimes new at their roles. They are trying to help you the best that they can, but they, themselves, are not always proficient in best practices for teaching multilingual learners. Not all feedback is good, but what is always good is a posture of humility: what can we learn from this person or situation? I know you feel the push of expectations from the administration. And with one hand, your leaders tell you: “Practice self-care,” but at the same time they say: “make sure to document your exchange hours,” and “You need to do these specific lessons in preparation for our state assessment,” “please use our new software to monitor student progress,” and, “be sure to be on time to our LONG faculty meetings.” I know that all of these things are falling hard on you because you are a perfectionist about your teaching practice. I’m sure you feel overwhelmed by all of these pressures, expectations, and distractions. I know that you often don’t feel seen for all that you are doing. And you wonder why other teachers seem to skate by doing so much less than you. Yet, you have a choice. You are doing great work. You are advocating for students who - without your presence in their lives - would be pushed to the margins. Perhaps they are told in other places that they do not matter. Perhaps they feel that their voices, their language, their culture, and their presence is not important. You are saying that it is. You are reversing long streams of colonialism buried deep in our country's fibers. You are working against the grain of all that would pull down these students and discourage them. And for this reason, you cannot allow all of the other junk and pressures in the teaching profession to get you down. Do not get weary of doing good. You must show up fresh, energized, and new for these students. And to do so, you may have to let some things go. Is it making the lessons really cute and beautifully designed? Is it trying to do all of the things for everyone? Is there a way that you could “reverse engineer” your schedule? This year my principal introduced the phrase: ‘strategically abandon.” I love that phrase because it means being intentional about what you are going to let go of to focus on the main thing. For me, I need to “strategically abandon” managing others’ expectations of me, and just do what I know I must: advocate for our students. What do you need to strategically abandon today, so that you can be “okay” for them? Here’s one I can help you with: you need to strategically abandon that appraisal, and not connect it with your identity. You are not a “proficient’ teacher - you are extraordinary!  The following narrative is written from the third-person omniscient point of view. Keep in mind that the teacher, working with a small group of students in the back of the classroom, does not have all of the information that you, the reader, do. January rolled in and it was time to prepare for State Testing. Isaiah Sanchez’s accomplished teacher differentiated instruction by grouping the class by their formative results. Naturally, the groups weren't labeled, but the students could discern the teachers' grouping by who was in each group. Isaiah was in the "at level" group, but he was bored and listening to the extension group tackle some math challenges he knew he could do. His friend Aiden (who never let anybody forget that he was in the gifted and talented program) was in the extension group and having a very interesting conversation. Isaiah wondered: why couldn’t he work with them? His teacher always told them to “challenge themselves.” Isaiah walked over to interrupt his teacher as she struggled through story problems in the "remediation group." “Ms. Teacher, I’m bored. Can I work with that group?” She signed. “No, Isaiah. Don’t worry about it, you’re fine. You approached the standard on the assessment.” Isaiah just stood there, frowning in protest. The teacher was eager to get back to her small group tutorials, and she didn’t tell Isaiah this, but she did not want him joining the group of high-performing students because she viewed him as a behavior issue, and expected him to get the other students off task. “You’re good!” She repeated. “You did as well as you could on the assessment.” “What do you mean?” Isaiah persisted. Now the teacher was getting frustrated with him. “You did as well as anyone would expect. Now please go sit down.” “...as well as you could,” “..as anyone would expect.” These words stuck in Isaiah’s mind as he begrudgingly trudged back to his desk. As he did so, his eyes traveled to his teacher’s desk, where for some reason, he saw his name handwritten on a list and “SPED” scrawled in big letters next to his name. He was confused. He knew he was only in the Special Education program because of his challenges articulating certain letter sounds. Perhaps his teacher knew something he didn’t? He glanced up to see Aiden smiling smugly at him. He must have overheard his conversation with the teacher because he mouthed: “DUMBY” to Isaiah. That was all it took. Isaiah stood up from silent reading with a growl and threw his desk across the classroom. The teacher stands up from her desk, shocked. This explosive behavior seemed to erupt out of nowhere! She orders Isaiah out of the room until she can figure out what to do. What was Isaiah attempting to communicate with his behavior? He did not consciously understand what he was feeling, or have the words to express it. But what was his behavior communicating? When we understand the child’s behavior as an expression of what they do not have words to say, we change our response to that behavior. We no longer try to shape their behavior, instead, we try to listen. When I was invited to visit a community outreach program in La Paz, Honduras, I jumped at the opportunity. Not only was I anxious to return to the country that felt like home, but I wanted to learn more about the educational system of some of my former students. For the past couple of years, I have welcomed immigrant students from Central America, who came to me preliterate in Spanish. I wondered why they were so behind when they had spent six years in the “sistema educativo” (public school system). For a week in July, I walked the cobblestone streets of La Paz, visiting families from the program in their casitas, playing with children on the playground, and facilitating lessons in social-emotional learning at the school. NiCo, which stands for Programa de Desarrollo Integral Niño—Comunidad (Program for Holistic Development of Children—Community) is a wrap-around program to serve the holistic needs of vulnerable children in the public school system of La Paz. Orphan Outreach, the nonprofit with whom we partnered with, describes the project this way: The children attending NiCo come from families living in extreme poverty. Most are broken families with high food insecurity and no access to clean water, electricity, and sewage infrastructure. NiCo seeks to help provide quality education and support services for children and families who are in need. Children attending NiCo have been recognized at their school not only for educational achievement but also for their strong character and leadership capabilities. (Orphan Outreach – Together We Can Restore Hope – Program, n.d.) The reason Nico was particularly interesting to me was because it partnered with the public school district to serve the needs of the most vulnerable children, and the public schools were reporting huge gains in these students’ performance. I was privileged to sit down with the Honduran directora of the program, Maria Lanza Colindres, and pick her brain about what was happening in public schools in La Paz, and what Nico was doing to support them. Here is a transcript of that interview, translated by me (with the help of Irene Zavala Lopez). Diaz: First of all, thank you for the amazing work that you are doing here! I want to let American educators know about what you are doing to meet the needs of vulnerable children, but first of all, can you tell me a little bit about the challenges you face?

Colindres: Of course. The students that we serve here in NiCo are the students who are several grade levels behind. Here in La Paz, teachers are under-resourced. They serve up to 40 students in their small classrooms, depending on the zone. In Honduras every four years the government changes, but the changes extend to the local level and even the curriculum in the public schools. In addition to these changes, there is so much staff turnover because we hire temporary teachers in the certification process, and they only stay three to four months. The bureaucracy here makes it almost impossible to submit the paperwork for certification, and the teachers must leave after four months if they aren’t certified (unless they have inside connections). But again, these connections change every four years. Diaz: Wow, that sounds very challenging. We are also having teacher staffing shortages and high turnover in the United States, but not to this level. What is the effect of this on students? Colindres: Although the government says something different, my experience is that kids are generally eight years behind where they should be in school. The Secretary of Education says that we cannot hold students back, so they are promoted even if they are not near grade level. Another problem children in La Paz work in coffee cultivation throughout the year, so they leave at inopportune times and then come back in April. All of this creates huge gaps in schooling. Diaz: How did Honduras handle schooling during the Pandemic? Colindres: All of the schools were closed during the Pandemic. We asked students to send in homework to their teachers with “WhatsApp,” but the majority of our students did not have access to this technology. Diaz: So how does NiCo meet these vast and seemingly insurmountable educational needs? Colindres: NiCo serves children in grades 1 - 6, by recommendation from the public schools. When students enter our program, we give them a diagnostic test to determine areas of deficiency. Unlike the US, Honduras does not have a special education program. Many of the children we serve here would qualify for such services. After testing, we provide personalized support and interventions for the child, based on their area of need. We move at the pace the child requires, sometimes this is very slow. Perhaps the diagnostic test reveals that the child does not know their letters, and then we begin there. Diaz: That sounds amazing. I love the personalized approach. What can you tell me about some of the progress you’ve seen? Colindres: I’ll tell you the story of one student in particular: Maria (name changed) came to us when she was in fifth grade, but she was functioning at the second-grade level academically, had problems with coordination, and was far behind in terms of her socio-emotional development. She was very withdrawn and acted more like a kindergartener than an older child. She could not write her own name when she came in. Part of the culture of NiCo is that we hold high expectations for students, but serve them with patience and respect. We also offer them the best therapy: “toda functiona con mucho amor.” We help them to change their narratives about who they are as students. Maria has been with us for four years. She can write her name correctly now. She knows her letters and is blending sounds. But the biggest difference is in her countenance: she is open and engaged with others.” Diaz: Yes! Maria has been really fun to interact with while I’m here. Speaking of changing that narrative, what is it I’ve heard all of the students say at the start of class each day? Colindres: Yo puedo, yo puedo hacerlo bien. Nadie es igual a mí. Soy única y especial (I can, I can do it well. No one is the same as me. I am unique and special). Diaz: Yes they can! Thank you for the extraordinary work you are doing to reinforce this message to vulnerable children! Dear New ESL Teacher,

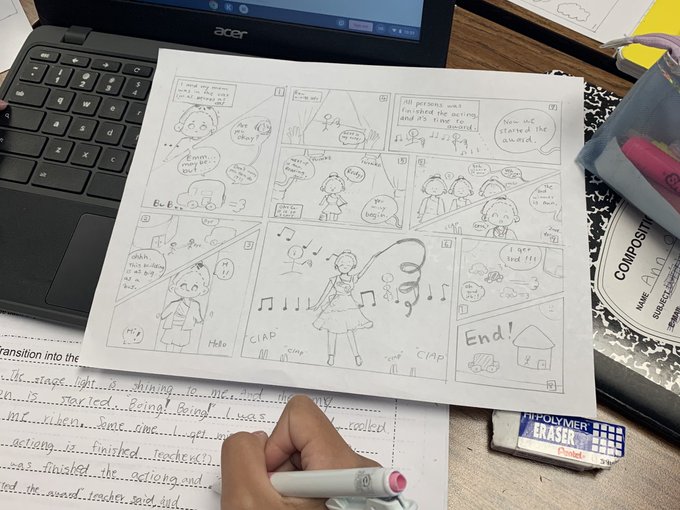

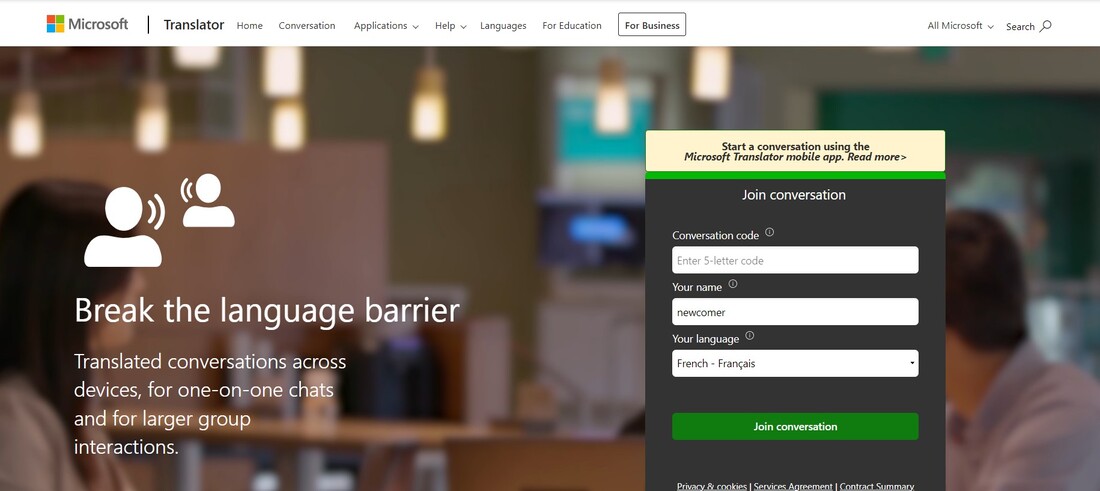

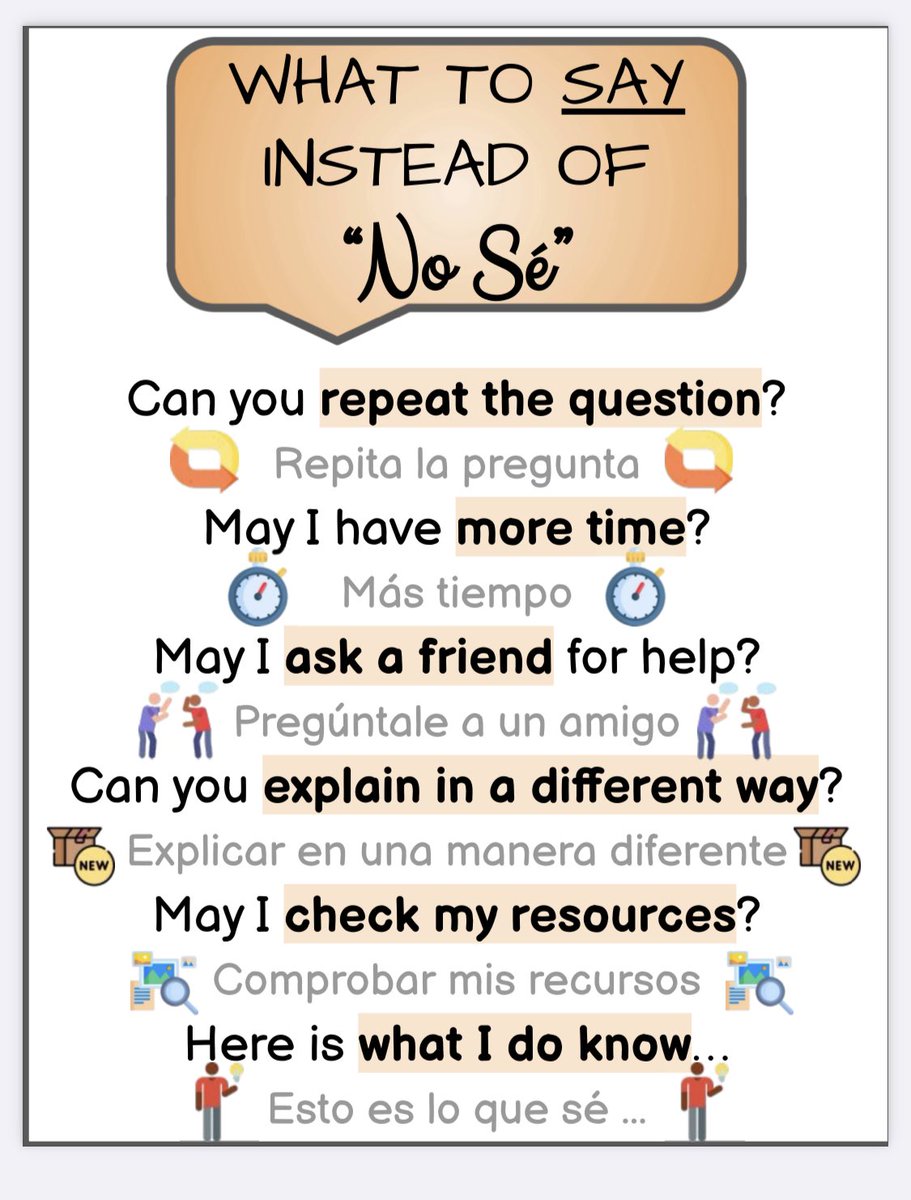

I know that you are counting the remaining days of summer and moving in a flurry to prepare for the school year. You have been quite preoccupied with the things around your classroom or office. As if the perfect location for that file cabinet would save you. I also imagine you pausing before the school supplies in Target, “Perhaps if I just had one more….” But one more flare pen and the perfect office organization won’t save you. The first day of school will hit you like a whirlwind. “ESL teacher to the front office, please.” “But wait - I wasn’t expecting them! Not now, I must…” And they will be there, blinking up at you: the hope of the world placed on your shoulders. “How do I register for class?” “What grade should I be in?” “Will the bus come to get me?” You may or may not know the answer to these questions. It doesn’t matter if you do or don’t. You represent that there is someone in their court in this new land. Somehow who knows how to navigate both worlds? Someone’s whose brain will ding like an alarm at the lunch hour, when you realize: “I forgot to ask them if they have lunch money! How are they even going to order lunch!” Then you will rush down to the cafeteria and see them snacking happily with a new friend. At that moment you will realize that you signed up to be an ESL teacher, but you are going to be so much more than that….and therein lies the beauty and the challenge. I must admit that I am a little jealous of you. I miss those awkward bowl cuts, bopping through the halls, delighted when they set eyes upon you. Enjoy them and their devotion, they will always remember you, and you them. Best of luck, Elise  Wouldn’t it be amazing if you spoke, and it went automatically into your newcomers’ heritage language, on their school laptop? This is, in fact, possible, with the Microsoft Translator App Step 1: Download the App on your phone. For the iphone, it looks like the picture at the bottom of this entry. Step 2: Start a new session on your phone. You should get a letter code (like TLGRC) that you will then give to your students to use on their laptops. Step 3: Help the newcomer to go to this website: https://translator.microsoft.com/ and to enter the code from your phone. Step 4: Confirm that it is working on your newcomers’ laptops. And that the newcomers know how to write messages back to you (these will pop up on your phone while you are speaking). Step 5: Speak at a normal speed and clarity into the phone. It will pick up EVERYTHING. No need to push the “microphone” button again. It keeps going. Know that this translation is most effective when combined with the regular comprehensible input you would give a newcomer (visuals and vocabulary support, touch to teach, and directions should still be given in a “short, imperative, pause” format. Watch the newcomer as you speak, to check for understanding. Just like Google translate, you may say a word such as “journal” and it may be translated as a noun, whereas you meant it as a verb. Lastly, know that “translation is a tool, not a teacher.” The student still needs you to support their language development, even if you are using Microsoft Translator effectively. Best of luck, and happy teaching!  Beginners tell their stories by illustrating a graphic novel. Each panel corresponds to a different element of plot (which they learned about read graphic novels and watching Pixar shorts). As they illustrate their stories, students point at their pictures and attempt circumlocution (a roundabout way of speaking if they don't have the vocabulary needed) to explain what is happening in the picture. The teacher helps them find the words: "Do you mean "ribbon dancing?" "Yes? This is how you write it." Then the student copies down the text she co-created with the teacher and practices reading it for fluency. This activity is wonderful for students learning the English language because it allows them to practice in each language domain (speaking, listening, writing, and reading), and also provides context to give meaning to the words they are discovering. This activity is effective for third grade through high school. Many panel options be found simply by googling: "graphic novel template." How would you incorporate an activity like this into your lesson planning? I talk to my own kids about what I'm doing in the classroom, probably too much. I do get a lot of good ideas from them. One time I was talking to my son and explaining the theory behind the "What to say instead of "I don't know," poster, which I encourage teachers to have in their classrooms. He remarked: "Mom, are you really training kids to say: "May I please have some more information?" (This was said sarcastically). "What, are they talking to the Queen of England? Is this a Charles Dickens novel?" (I wish!) He went on:

"I hate it when teachers correct me when I'm asking to go to the bathroom ("May I..") He's actually not wrong in this criticism. Linguist Stephen Krashen describes how ineffective it actually is when we teachers correct students' grammar in the classroom in this way, but I'm getting off-topic. My son's point is that he wanted to give students the meta-cognitive tools to think about why they don't know the answer, or what they need to find the answer, but spoken in their own way. Since that fateful conversation, I have been encouraging teachers to NOT put up the standard "Instead of "I don't know poster." Instead, to make the poster along with their students. One teacher I worked with in Texas (Dominque Phifer), created this beautiful poster (above) for her newcomer, predominantly Spanish-speaking classes. When teachers make their own posters with and for their students, the responses vary. Sometimes the poster might say something as simple as "Help, please" (if you have a newcomer just at the starting line of language learning, with a very high affective filter). Or perhaps the poster says: "Point to what you need." The point of these posters is to teach students a metacognitive skill and to remind teachers every student has the capacity to find the answer, with support. My son was right (although I would enjoy everyone around me speaking as if it was 18th-century England). Sometimes we get lost in the product and forget about the process. SWAP Out the "American" Names for Common Names in Your Students' Cultures

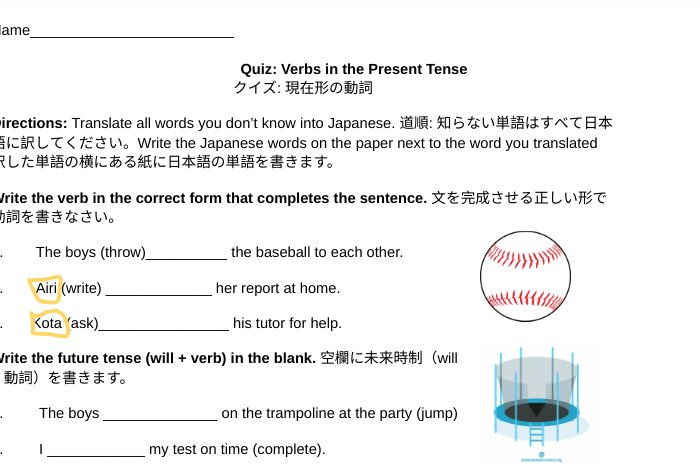

When accommodating a quiz for newcomers, swap out the "Heather's" and "Brian's" in your examples for common names in their culture. One less word to translate, and helps them feel a greater sense of belonging. There are so many times I have been helping a newcomer read a grade-level text in their core classes, and they ask me: "What is a 'Stacy'?" This is a very easy thing for teachers to do, and that has a great impact! |

AuthorElise White Diaz is an Educational Consultant with Seidlitz Education, specializing in trauma-informed multilingual education. CategoriesArchives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed